New Year’s Day morning, 1983, dawned cold and rainy in Dallas, but Tom Flynn had seen worse.

He grew up in western Pennsylvania and had played in similar conditions at Penn Hills High School and Pitt. Later, he played in snowstorms with the Green Bay Packers.

Truth be told, the weather in Dallas was a minor annoyance. Flynn was just eager to play another football game — and seek redemption.

Yet there was a problem: The pain in his foot had returned.

Pain.

That word helps describe what the 1982-83 Pitt football team endured before and during that game against SMU in the Cotton Bowl. It was not always of the physical variety.

Another word also fits:

Talent.

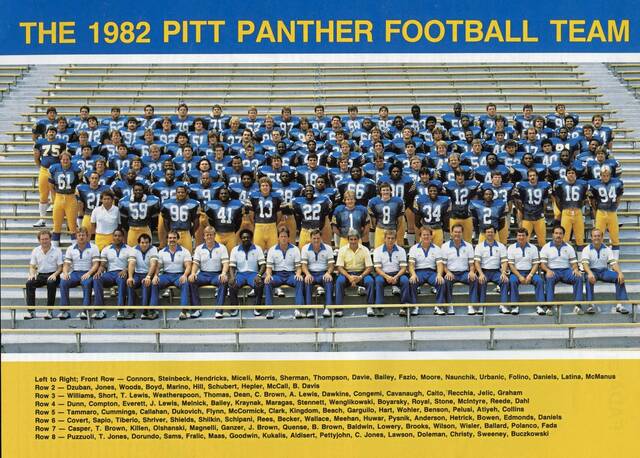

Accompanied by great expectations, 18 of 22 starters returned from the previous season when Pitt had concluded an incredible string of 33 victories in 36 games. Six became NFL first-round draft choices. Dan Marino, Jimbo Covert and Chris Doleman are in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Pitt started out No. 1 in the nation, according to the polls, but finished No. 10 with a 9-3 record after losses to Notre Dame and Penn State and 7-3 to SMU.

Longtime sportswriter, columnist and Pitt grad Bob Smizik had a front-row seat that season as the beat writer for The Pittsburgh Press. He pulled no punches when he recently told TribLive, “That is the most disappointing team in the history of the University of Pittsburgh.”

Added author and Pitt historian Sam Sciullo Jr.: “The ’82 team was virtually the same as ’81, but was a year older and more experienced. The ’81 team was a year away from what should have been greatness.”

The 2024 Pitt Panthers, who are 7-0 for the first time since 1982, will play another high-profile game in Texas — also against SMU — next Saturday in Dallas. When No. 19 Pitt plays No. 22 SMU, the stakes won’t be quite as high as they were 42 years ago, but a victory would launch the winner into serious discussion regarding a berth in the ACC Championship game.

There was no conference for Pitt in 1982, and a 12-team playoff to determine a national champion would have been considered an outrageous luxury for fans. Two defeats — 31-16 to coach Gerry Faust and Notre Dame on Nov. 6 and 19-10 to eventual national champion Penn State at Beaver Stadium on Nov. 26 — ended Pitt’s title hopes.

Marino was injured for part of the season, and he did not play as well as he did in 1981 when he threw 37 touchdown passes, including the game-winner to Burrell’s John Brown that beat Georgia in the Sugar Bowl. In fact, Marino was not on the field for a touchdown in the final two games of his collegiate career, having been injured and on the sideline briefly when Pitt scored against Penn State.

Baseless rumors about drug use swirled around Marino, too. To the extent that during the telecast, CBS sideline reporter Pat O’Brien defended Pitt’s quarterback against those falsehoods.

“He has had pressure from the press from Day 1,” O’Brien said, “right after his first game (a 7-6 victory against North Carolina at Three Rivers Stadium). Now, in Dallas this week … we’ve read some very vicious things written about this youngster. You have to wonder how these 19-, 20-, 21-year-old kids can go out here and play football and open the paper the next day and read these things written about them. It’s a tribute to them that they are out here playing a pretty good, tough football game.”

Tragedy strikes

The days leading up to the Cotton Bowl were difficult ones for Pitt’s players and coaches.

The night before the team left for two weeks in Dallas, sophomore linebacker Todd Becker died when he fell from a third-story window at Brackenridge Hall, a campus dormitory. Becker was attending a toga party, but he had been banned from the dorms for spraying a fire extinguisher the year before. When someone at the party recklessly set off a fire alarm, campus police arrived, Becker got scared and tried to leave through a window.

“He had no fear,” first-year coach Foge Fazio told Sports Illustrated. “I’m sure he thought. ‘This is easy for me. I can do this. I’ll jump down and be practicing tomorrow.’ “

Secondary coach Dino Folino said the tragedy created a “pall hanging over your head all the time.”

“It really cast a shadow on everything. He had great friends on the team. He was a character that kept people laughing and kept them on their toes.”

Said nose tackle J.C. Pelusi: “You can’t even put that into words, the impact. I wouldn’t think it had anything to do with us winning or losing, but it certainly was traumatic for a young team like that. Players and coaches flew from Fort Worth to the funeral. I think about that (to this day), tragic.”

Pitt won its first seven games, largely in unremarkable fashion when fans expected better victories than 16-13 against West Virginia and 14-0 over Syracuse.

October 2, 1982: Pitt’s @DanMarino throws the game-winning TD pass to Julius Dawkins, and the Panthers beat West Virginia 16-13 in the Backyard Brawl.

Pitt trailed 13-0 early in the 4th quarter.

pic.twitter.com/wBTMplml5k— This Day In Sports Clips (@TDISportsClips) October 3, 2024

Pelusi, the last of three Pelusi brothers to play for Pitt, said, “That season, I just don’t think we progressed as well as we needed to. I don’t want to blame it on coaching because we were the players. I don’t know if we dominated as well as we could have dominated that year.”

Folino, recently retired after a long career in coaching and administration at Michigan State, said the problem started before the season.

“I think it started the year before when we lost two key ingredients to having a great football program. We lost coach (Jackie) Sherrill and (athletic director) Cas Myslinski,” said Folino, a Central Catholic graduate.

Sherrill left for Texas A&M after the 1981 season and Myslinski retired in April, 1982.

“Cas should get a lot more credit than people think about because he brought Pitt back. He hired John Majors,” Folino said. “A lot of those great players were recruited because of Jackie.

“They bought us blazers to wear in recruiting. Navy blazer with a little script Pitt on the pocket. You could go into any school and the kids would run over to talk to you. We could recruit against anybody. Jackie hired a staff of guys who wanted to be at Pitt. That became a destination job.”

Of Sherrill, the 75-year-old Folino said, “I’d go to work for him tomorrow.”

Fazio, a Pitt grad, was promoted from defensive coordinator to replace Sherrill, but was fired after four seasons, including records of 3-7-1 and 5-5-1 in 1984 and 1985. Fazio, who died at 71 in 2009, had two years left on his contract when he was terminated. He immediately resumed a successful coaching career, including time spent with Notre Dame and four NFL teams.

“I don’t think Foge got the support (from the administration) that he would have had with Cas,” Folino said.

Former Pitt coach Dave Wannstedt said of Fazio immediately after he died, “Foge was a true ‘Pitt Man.’ He loved this university and everyone at Pitt loved Foge.”

Pelusi remembers getting called into university assistant president Ed Bozik’s office when news of Sherrill’s departure was released. Bozik oversaw the athletic department and, eventually, replaced Myslinski.

“He was asking me about Foge,” Pelusi said. “I said Foge is a tremendous guy, great coach. But one of the things you have to be careful of is he’s very friendly and buddy-buddy with everybody.

“Jackie was (very much a) disciplinarian. I think Jackie modeled himself after Bear Bryant to some extent. Foge was always the coach we turned to in tough times when he was an assistant coach because he was our friend. I think that was a tough transition for him.”

Plus, Fazio coached under the weight of high expectations. “Maybe too high,” CBS analyst Pat Haden said during the telecast.

Locker room unrest

Before the team left for Dallas, stories of discontent in the locker room were published in the Pittsburgh Press and Dallas Times Herald.

Mark Hyman of the Times Herald arrived in town to do a story on SMU’s opponent, and left with quotes from Pitt players he didn’t expect.

“I knew the (Pitt) sports information staff,” said Hyman, now the director of the Sports Journalism Center at the University of Maryland. “With their help, I set up a meeting with the players.”

Starting offensive guard Ron Sams, an Academic All-American, and Lewis were critical of All-American wide receiver Julius Dawkins. Sams told Hyman, “We expected him to do a great job for us this year, but for some reason he wasn’t getting open like he should. I’m trying not to be critical. But I don’t think he put 100% concerted effort into trying to win every ballgame. It just upsets me.

“We’re all not perfect. But you can bet that the five (Pitt) offensive linemen in the game are giving a minimum of 100% every time we step on the field.”

Said Lewis: “He does what he wants when he wants. And if he thinks he’s going to get crushed (by a defensive back) jumping up to catch a ball, there’s no way he’s going to jump. He’ll get out of the way and let it go.”

Added Dawkins of Sams: “If he was doing his job he wouldn’t be worried about what I’m doing.”

Before publishing the story, Hyman spoke to Smizik to put the comments in context.

Smizik, in turn, went back to the players and received similar quotes.

“They were a little more reticent this time because they knew we were up to something,” said Smizik, now retired. “But they did not deny what they had told Mark earlier.”

Pitt called a news conference in response to the stories, but Hyman said the furor disappeared when the team arrived in Dallas.

“Really, it was over in a few days,” he said. “Nobody was really talking about that, and I didn’t have any trouble dealing with players on either team as a result.”

Under difficult circumstances — hateful, unfounded rumors about its star quarterback, unhappy players, a disappointing regular season and the Dallas weather — the Cotton Bowl became the Pitt seniors’ last hope of saving the season.

Defense takes a stand

Defensively, Pitt hardly could have played better. Pelusi recorded 20 tackles and Flynn, a four-year starter at safety, linebacker Rich Kraynak and Lewis made plays all over the field.

“We might get outplayed, but we always tried to be the most physical team on the field,” Flynn said.

Folino said the defensive line of Dave Puzzuoli, Pelusi, Bill Maas and Doleman — the latter two first-round draft picks — had a slogan. “Their theme, always, unwritten and unspoken, was win, lose or tie, our opponents are going to limp out of the stadium.”

The day didn’t start well for Flynn.

“I woke up the morning of the game and my foot hurt,” he said. “I look outside and it was raining, 35 degrees. Nothing’s worse than that for a football game, cold and wet. It was an old field and we were slipping around a lot. You were trying to cut and your feet would come right out from under you.”

Yet foot pain was hardly an issue, Flynn said. “We learned to play with pain.”

SMU came into the game undefeated with only a 17-17 tie with Arkansas soiling its record. Reports of SMU players getting paid led to the school getting the “death penalty” and having its 1987 and 1988 seasons canceled. When the program returned in 1989, the Mustangs had one winning season through 2008 before finally getting back to a bowl game in 2009. They defeated Pitt in the BBVA Compass Bowl after the 2011 season and were American Athletic Conference champions in 2023 before joining the ACC this year.

Folino said Pitt’s players were aware of the allegations surrounding SMU, but they ignored the noise.

“There was very little talk about SMU being the best team money could buy,” he said. “We just wanted to line up and play against a great team, show how good we are.”

SMU running back Craig James, who famously teamed with Eric Dickerson to form the Pony Express backfield, said those charges grew from jealousy.

“The jealousy came from (Texas) Longhorns and others who couldn’t beat us consistently,” he said. “When, in fact, they were doing the exact same thing we were doing — the ultimate of hypocrisy.

“Eric and I, we’re very close friends to this day. We know what was going on back then (in recruiting). It wasn’t just in Dallas.”

James, who went on to successful careers in broadcasting and real estate and an unsuccessful run for the U.S. Senate against Ted Cruz in 2012, remembers the game’s physicality.

“I can remember one time going up into the line and getting tackled and remembering just how violent it was,” he said. “I caught a pass down the middle, pretty long throw, and (I said), ‘This ball better hurry up and get here because I know they’re coming.’

“If you’re a Pitt fan, you wish it had been dry so they could have seen how it might have been with throwing the ball. If you’re a Mustangs fan, we’d like to be able to run the option on the corners. It would have been completely different. Both teams had to play out of the normal character.”

The game’s only touchdown was a 9-yard run by quarterback Lance McIlhenny from a four-man backfield. He faked a handoff to Dickerson and a pitch to James before cutting inside the flowing Pitt defense for the score.

With cold rain and sleet falling, Pitt center Jim Sweeney at one point can be heard on the YouTube.com video angrily calling for a “new ball.” In the end, dropped passes and an end zone interception contributed to Pitt’s smallest point total since a 17-0 loss to Navy in 1975.

SMU came into the game seeking a national championship, left 11-0-1, but had to settle for No. 2 behind Penn State, which beat Georgia in the Sugar Bowl but earlier had lost to Alabama, 42-21.

Pelusi said he doesn’t like losing or talking about losing, but he still likes what he sees when he looks back on his Pitt career. Despite all the victories and success, he felt like just another student.

“When you’re in it, you don’t realize it until you look back,” he said. “It’s not like today. It wasn’t 24/7 football on TV, talk shows and all that stuff like it is now. We were just normal students and student-athletes in its truest sense. Walking up the hill for football practice around 2 o’clock in the afternoon, watching film and then practicing and going to the training table.

“You realize you had a good team, but it wasn’t the constant talk. You were just enjoying it and probably didn’t put it in the perspective of how good of a team you were.”

The Cotton Bowl experience was special for Folino, who welcomed the birth of daughter Ellen — one of his eight children — in Dallas days before the game. He said he’s proud to say Ellen was delivered by a Pitt-educated doctor Dec. 28, 1982.

When discussing the game and that Pitt team, however, Folino broke one of his long-standing rules.

“My belief, still is, you only deserve to win when you win,” he said. “But the better team lost that day.”

Jerry DiPaola is a TribLive reporter covering Pitt athletics since 2011. A Pittsburgh native, he joined the Trib in 1993, first as a copy editor and page designer in the sports department and later as the Pittsburgh Steelers reporter from 1994-2004. He can be reached at [email protected].